Dating the Crucifixion

This article is abbreviated from one appearing in Nature Magazine, December 1983, by Colin J. Humphreys and W.G. Waddington. (Square brackets indicate BT editorial comments.) In this study astronomical calculations have been used to reconstruct the Jewish calendar in the first century AD and to date a lunar eclipse that Biblical and other references suggest followed the crucifixion. The evidence points to Friday 3 April AD 33 as the date when Jesus Christ died.

The only certainty about the date of the crucifixion is that it occurred during the 10 years that Pontius Pilate was procurator of judaea (AD 26-36). [On this] Tacitus (Annals XV, 44) agrees with the four gospels. All four gospels agree that Jesus died a few hours before the beginning of the Jewish sabbath (nightfall on a Friday) and – within a day – that it was the time of the Passover, the annual Jewish feast held at the time of a full moon.

Passover time was precisely specified in the official festival calendar of Judaea, as used by the priests of the temple. Lambs were slaughtered between 3:00 p.m. and 5:00 p.m. on the 14th day of the Jewish month Nisan (corresponding to March/April in our calendar). The Passover meal began at moonrise that evening, at the start of 15 Nisan (the Jewish day running from evening to evening).

– Leviticus 23:5, Numbers 28:16

Some scholars believe that all four gospels place the crucifixion on Friday, 14 Nisan [this is the common view of the brethren], and others believe that, according to the Synoptics, it occurred on Friday, 15 Nisan. For generality, we assume at this stage that both dates are possible and set out to determine in which of the years AD 26-36 the 14th and 15th Nisan fell on a Friday. Previous attempts’ to use astronomy to resolve this ambiguity have shown that while the times of new and full moons can be accurately specified, we do not know with what skill the Jews of the first century could detect the first faintly glowing lunar crescent after conjunction with the sun. (The new moon itself is invisible by definition.)

JEWISH CALENDAR

Hitherto it has been customary to assume arbitrarily that the sickle of the new moon would be invisible to the unaided eye until a certain length of time (usually 30 hours) had elapsed since conjunction. Fotheringham’s more realistic criterion, based on the apparent position of the moon in the sky at sunset, was modified and improved by Maunder, but even that criterion is not rigorous, excluding several thin crescents that have been observed.

We have therefore computed the visibility of the lunar crescent as a function of time after sunset for the beginning of each lunar month in the period of interest. Whether or not the crescent moon is visible depends on whether its contrast with the sky background exceeds the visual contrast thresholds The lunar semidiameter and the position of the moon in the sky at and after sunset have been evaluated from harmonic syntheses of the perturbed orbits of the Earth and moon and the sky brightness for an observer at Jerusalem calculated as a function of the depression of the sun below the horizon, as is the mooiys apparent surface brightness. At the latitude of Jerusalem, we find that the lunar crescent is first visible after sunset at a lunar altitude corresponding to approximately 0.5o less than that given by Maunder and this is consistent with many recent observations of the first sickle of the new moon. Assuming normal atmospheric transparency, we obtain the results of Table 1.

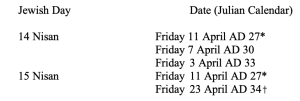

Table 1. The date of 14 Nisan in Jerusalem, AD 26-36.

The time of new moon is given as calculated apparent (sundial) time of conjunction for Jerusalem (± 5 min). The deduced rate is the Julian day (from midnight to midnight), starting at 6th hour 14 Nisan and ending at 6th hour 15 Nisan.

* 14 Nisan AD 27 and AD 32 could have been on the following day if the new moon was not detected due to poor atmospheric transparency.

† ln each of these cases it is not impossible, but highly improbable, that 14 Nisan would have occurred on the preceding day.

Although in the first century AD the beginning of the Jewish lunar month (in the official calendar) was fixed rigorously by astronomical observation, difficulties arise because of the Jewish use of intercalary (or leap) months. Twelve lunar months total approximately 11 days less than a solar year, but for agricultural and ritual purposes, lunar months were kept at roughly the same place in the solar year by the intercalation of a thirteenth month when necessary, roughly once every three years. In the first century AD, intercalation was regulated annually by proclamation by the Sanhedrin according to certain criteria,3 one of the most important of which was that Passover should fall after the vernal equinox. If, towards the end of a Jewish year, it was estimated that Passover would fall before the equinox, the intercalation of an extra month before Nisan was decreed. Table 1 has been constructed on this basis.

Unfortunately, a leap month could also be decreed if the crops had been delayed by unusually bad weather (since the first fruits must be ripe for presentation on 16 Nisan) or if the lambs were too young. There are, however, no historical reports of the proclamation of leap months in the years AD 26-36, so that it is possible that in some years Nisan was one month later than given in Table 1. Calculations show that in the period AD 26-36, if Nisan was one month later than given in Table 1, 14 Nisan would not fall on a Friday in any year and 15 Nisan would fall on a Friday only in AD 34 (April 23).

Table 2 lists all the possible dates of a Friday crucifixion falling on either 14 or 15 Nisan. These are the only dates that are astronomically and calendrically possible for the crucifixion. We now consider which of them can be eliminated by means of other available evidence.

Table 2. Calendrically Possible Dates for the Crucifixion.

*There is some uncertainty, depending on the atmospheric conditions, as to whether this day was on 14 or 15 Nisan (see text and Table 1). We include all possibilities for completeness.

†Only in the case of a leap month being inserted because of exceptionally severe weather (see text).

FURTHER EVIDENCE

AD 27 is almost certainly too early. Luke 3:1-2 carefully states that John the Baptist began his ministry in the fifteenth year of Tiberius Caesar and subsequently baptized Jesus. Depending on whether the Hellenistic (Roman) civil or the Jewish ecclesiastical reckoning is used, the fifteenth year (340 Seleucid Era) would either have been autumn AD 28-29 or spring AD 29-30.4 In addition, most scholars believe that Pilate had been procurator for some time before the crucifixion (see Luke 13:1, 23:12).

Similarly, AD 34 is almost certainly too late, for it would conflict with the probable date of Paul’s conversion. We can fairly confidently date the later events in Paul’s life and, working back from these using time intervals given by Paul himself (for example Galatians 1:18, 2:1) leads many scholars to infer Paul’s conversion was in AD 34. Moreover, AD 34 is only a possible crucifixion date if the weather that spring had been exceptionally severe. There is therefore no positive evidence in favor of AD 34 and we exclude it. (The only eminent advocate of 23 April, AD 34 that we have come across is Sir Isaac Newton, whose chief reason seems to have been that 23 April is St. George’s Day.)

Having eliminated AD 27 and AD 34, we note from Table 2 that the crucifixion must have occurred on 14 Nisan. We remark that by this means, a scientific argument has … shown that the crucifixion occurred on 14 not 15 Nisan, so that Jesus died at the same time as the Passover lambs were slain. This is consistent with many New Testament statements such as “Christ our Passover is sacrificed for us.” (1 Corinthians 5:7)

By elimination, AD 30 and AD 33 are now the only two plausible dates for the crucifixion. The earliest possible time at which Jesus can have begun his ministry is autumn AD 28, while John’s gospel records three different Passovers occurring in the ministry (including that at the crucifixion). If this evidence is accepted, AD 30 cannot be the crucifixion year and AD 33 is the only possibility.

This is also consistent with the reference in John 2:20 which records that the Jews said to Jesus at the first Passover of his ministry that the temple had taken 46 years to build. Assuming that this refers to the inner temple,5 the 46 years leads to AD 30 or 31, depending on how much preparation time was involved before building began. If the only Passovers of Jesus’ ministry were the three explicitly mentioned in John’s gospel, an AD 33 crucifixion implies a ministry of about 21/2 years. Many scholars, however, believe that John omitted to mention a further Passover, in which case the ministry would have lasted for 3½ years. [And this length is supported by Daniel 9:27.]

A LUNAR ECLIPSE

We now consider further evidence that has not, to the best of our knowledge, been used in helping to date the crucifixion – the subsequent occurrence of a lunar eclipse. [Actually the eclipse at issue had been noted by some brethren more than twenty years ago.]

We first take up the meaning and significance of the references to the moon being “turned to blood” in the Bible and also in the Apocrypha.

In Acts 2:14-21 it is recorded that on the day of Pentecost, the apostles were accused by a crowd of being drunk and that Peter stood up and said “No, this is what was spoken by the prophet Joel: In the last days, God says, I will pour out my spirit on all people … I will show wonders in the heavens above … The Sun will be turned to darkness and the moon to blood before that great and glorious day of the Lord shall come.”

It is not clear whether Peter was claiming that all the quoted prophecy from Joel had recently been fulfilled … but in our view, the phrase “the moon turned to blood” probably refers to a lunar eclipse, in which case the crucifixion can be dated unambiguously.

Peter prefaces his quotation from Joel with the words “Let me explain this to you … this is what was spoken by the prophet Joel ‘ “ He appears to be arguing that recent events had fulfilled the prophecy he was about to quote. If this interpretation is correct, “the last days” began with Christ’s first advent (cf 1 Peter 1:20, Hebrews 1:1-2), the outpouring of the spirit commenced at Pentecost, and “that great and glorious day” refers to the resurrection. “The sun will be turned to darkness” (v. 20) refers back to the 3 hours of darkness which occurred only 7 weeks previously, at the crucifixion (Matthew 27:45), and would be understood as such by Peter’s audience.

As is well known, the mechanism by which the sun was darkened may have been a khamsin dust storm. Since the darkened sun occurred at the crucifixion it is reasonable to suppose that “the moon turned to blood” occurred that same evening, “before that great and glorious day,” the resurrection. [The “great and terrible day” of Joel 2:31 may actually refer to the end of the nation some decades later.]

Other documentary evidence suggests that on the day of the crucifixion, the moon appeared like blood. The so called “Report of Pilate,” a New Testament Apocryphal fragment,6 states that at the crucifixion “the sun was darkened; the stars appeared and in all the world people lighted lamps from the sixth hour till evening; the moon appeared like blood” Although much of the Apocrypha cannot be used as primary historical evidence, Tertullian records that Pilate wrote a report of all the events surrounding the crucifixion for the Emperor Tiberius. The manuscript fragments of the “Report of Pilate” are all of a later date, but may be partly based on the lost original.

On the other hand, the report may have used the Acts as a source, in which case it may be significant that the event described by Peter in which the moon turned to blood is clearly stated to have occurred at the crucifixion.

It is of course also possible that the report is a late Christian forgery, but even such a document may be thought to reflect a widely held contemporary belief. In other words, the “Report of Pilate” is secondary supporting evidence that the moon appeared like blood on the evening of the crucifixion.

THE MOON TURNED TO BLOOD

The reason an eclipsed moon is blood red is well known. Even though the moon is geometrically in the Earth’s shadow, sunlight still reaches it by refraction in the Earth’s atmosphere and is reddened by having traversed a long path through the atmosphere where scattering preferentially removes the blue end of the spectrum.

Descriptions of some well documented ancient eclipses have been compiled … and matched with calculated eclipse dates. We quote three examples: (1) The lunar eclipse of 20 September 331 BC occurred 2 days after Alexander crossed the Tigris and the moon was described by Curtius (IV, 10 (39), 1) as “suffused with the colour of blood.” (2) The lunar eclipse of 31 August AD 304 (probably) which occurred at the martyrdom of Bishop Felix, was described in Acta Sanctorem “when he was about to be martyred the moon was turned to blood.” (3) The lunar eclipse of 2 March AD 462 was described in the Hydatius Lemicus Chronicon thus: “on March 2 with the crowing of cocks after the setting of the sun the full moon was turned to blood” In … mediaeval European annals … many lunar eclipses are described by “the moon turned to blood.”

LUNAR ECLIPSES VISIBLE IN JERUSALEM AD 26-36

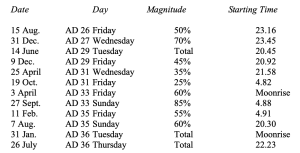

We have determined the eclipses relevant to our work by the use of the most comprehensive data available, as corrected by Stephenson,7 in the light of Babylonian records and long-term changes in the Earth’s rate of rotation. All lunar eclipses (total and partial) visible from Jerusalem between AD 26 and AD 36 are listed in Table 3 which shows that in the period AD 26-36, there was only one lunar eclipse at Passover time visible from Jerusalem.

Table 3. Lunar Eclipses Visible from Jerusalem AD 26-36.

The date Friday, 3 April AD 33, is the most probable date for the crucifixion deduced independently using other data. The interpretation of Peter’s words in terms of a lunar eclipse … allows us with reasonable certainty to specify Friday, 3 April AD 33 as being the date of the crucifixion.

VISUAL APPEARANCE

All times quoted below are local Jerusalem times as measured by a sundial, and the probable error in the eclipse times is about ? 5 minutes. The start of the eclipse at 3:40 p.m. was invisible from Jerusalem, being below the horizon. At its maximum at about 5:15 p.m., with 60% of the moon eclipsed, the eclipse was still below the horizon from Jerusalem. The moon rose above the Jerusalem horizon at about 6:20 p.m. (the start of the Jewish Sabbath and also the start of Passover day in AD 33) with about 20% of its disk eclipsed and the eclipse finished some 30 minutes later at 6:50 p.m..

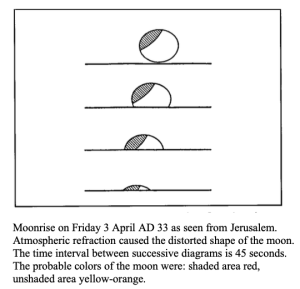

Although at moonrise only 20% of the total area of the moon’s disk was eclipsed (in the umbral shadow), this “bite’ was positioned close to the top (leading edge) of the moon. The drawing below shows the appearance of the moon at, and shortly after, moonrise at 3 April AD 33. As the umbral shadow (in which the sun is geometrically entirely hidden) was near the top of the moon, about 65% of the visible area of the rising moon would initially have been seen as fully eclipsed, while the remainder would have been in the penumbral shadow.

The coloration of eclipses varies greatly with atmospheric conditions. For partial eclipses, particularly with the moon at high altitude, there is a large contrast difference between the obscured and unobscured part of the disk so that the moon often appears almost white with a very dark “bite” removed. However for some partial eclipses the red colour of the umbral shadow is clearly visible. For example, Davis8 has recently depicted in colour an eclipse sequence as seen by the human eye with the moon low in the sky, when the blood red of the umbra in the partial eclipse phase is almost as vivid as when the eclipse is total.

For the eclipse of 3 April AD 33, the moon was just above the horizon and the most probable colour of the visible portion would have been red in the umbral shadow (shaded in Figure 1) and yellow-orange elsewhere. The small yellow-orange region would have indicated that the moon had risen, but most of its visible area would have “turned to blood.” If in fact a massive dust storm was responsible for darkening the sun a few hours previously, dust still suspended in the atmosphere would have tended to modify these colours, probably further darkening and reddening the moon.

The eclipse of 3 April AD 33 would probably have been seen by most of the population of Israel, since the Jews on Passover Day would be looking for both sunset and moonrise in order to commence their Passover meal. Instead of seeing the expected full Paschal Moon rising they would have initially seen a moon with a red “bite” removed. The effect would have been dramatic. The moon would grow to full in the next half hour. The crowd on the day of Pentecost would undoubtedly have understood Peter’s words as referring to an eclipse which they had recently seen.

1 J. Jeremias, The Eucharistic Words of Jesus, London, 1966. J.K. Fotheringham, Journal of Theological Studies, 35, 146, 1934. H.H. Goldstine, New and Full Moons, 100 BC to AD 1651, Fortress, Philadelphia, 1973.

2 G.H. Kornfeld, WR. Lawson, J. Opt. Soc. Am., 61, 911 (1971).

3 E. Schurer, G. Vermes, F. Millar, The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ , Vol. 1, Edinburgh University Press, 1973. G. Ogg, The Chronology of the Public Ministry of Jesus , Cambridge University Press, 1940.

4 O. Edwards, Palest. Explor. Q., 29, 1982.

5 H.W. Hoehner, Chronological Aspects of the Life of Christ , Zondervan, Grand Rapids, 1977.

6 M.R. James, The Apocryphal New Testament, 154, Clarendon, Oxford, 1953.

7 T.R. Oppolzer, Canon of Eclipses, 1877, translated O. Gingerich, Dover, New York, 1961. F.R. Stephenson, D.H. Clark, Applications of Early Astronomical Records , Oxford University Press, 1978. F.R. Stephenson, Scientific American, 247 (4), 154, 1982.

8 D. Davis, Sky Telescope , 64, 391, 1981.