Why Waldo?

“I know thy works, and charity, and service, and faith, and thy Patience, and thy works; and the last to be more than the first” (Revelation 2:19).

Of all the messengers to the seven stages of the Church, one of whom we know little was the fourth, Peter Waldo, for records of him and his work are scant from this dark period of the Church when Papacy was strong. Why Waldo? Our study is to answer that question.

The fourth stage of the church is Thyatira. It covers the period from about 1160 to 1378, around 220 years, and we suggest its messenger was Peter Waldo.1 He was a wealthy merchant, born in Lyon, France in 1140 and died in 1217.2

WALDO’S LIFE, TWO DIFFERENT ACCOUNTS

There are two different accounts about how Waldo began his Christian service. In the first, Waldo was in conversation with several principal citizens of Lyons, when suddenly one of his companions fell to the ground and died. This experience affected Waldo profoundly. He reflected on the mortality of man and the death penalty upon the human race, amended his life, and became more diligent in the fear of God.

Waldo began to distribute his wealth to the poor and discuss the virtues of goodness with others at every opportunity. He desired to understand the Holy Scriptures better, but he could not read Latin. So he employed a priest to translate the four Gospels and other books of Holy Writ from Latin into French. After diligent study, he concluded that the best way to follow Christ and the apostles was to abandon his business vocation and distribute his riches. He publicly preached the doctrines and precepts of Christianity, emphasizing the importance of doing good and living a pure and simple life as in the early church.

His preaching motivated many of his neighbors and countrymen, who joined themselves to Waldo and followed his example, divesting themselves of earthly riches and devoting their lives to preaching the Gospel. These became known as the “Poor Men of Lyons,” and the movement came to be known as the Waldenses.

Peter Waldo

A second, different account, is this. By the year 1173, Waldo at 33 had made a lot of money, possibly much of it by the practice of usury. One Sunday Waldo heard the story of the legend of St. Alexis from a traveling troubadour. Alexis was the privileged son of a 4th Century Roman senator of enormous wealth and power. He left his wealth and his wife in order to embark on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land and afterward devoted his life to care for the poor.

Waldo was so smitten by the story that the next morning he hurried to the nearest school of theology to seek counsel concerning his eternal destiny. He learned about many ways of going to God, so he asked what was the most certain one. They directed him to Matthew 19:21, “If thou wilt be perfect, go and sell all that thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven: and come and follow me.” Waldo embraced this, so he went to his wife and gave her the choice to keep either his money or his vast real estate holdings. Of course she was much displeased with having to make such a choice, but seeing that she had to choose, she kept the real estate.

From his wealth, Waldo first made restitution to any he had treated unjustly. He then gave a large amount of money for the life-long support of his little daughters, placing them in the exclusive convent of Font Evrard, reserved for the very wealthy. But the largest sum of his money he gave to the poor. During this time there was a famine in the land, and he gave food to everyone that came to him. While he was divesting himself of his wealth, he also paid to have the Latin Bible translated into the common French dialect of his day.

THYATIRA

Thyatira was renowned for its production of costly red and purple dyes for the rich, or royalty. It is interesting that Babylon the Great, the mother of harlots, was “arrayed in purple and scarlet color” (Revelation 17:4). Thus it is appropriate that this city, possessing these characteristics of royalty, symbolized the fourth stage of the church. Papacy had reached its zenith of power, both civil and religious. While the true church suffered hardship in the wilderness, the Papal church sat on the throne with the kings of the earth.

“Thyatira” means “sweet perfume of sacrifice, slow burning incense or sacrifice under duress.” This definition fits because God’s people during the fourth stage of the church suffered severe persecution. The saints of Thyatira were submissive under these crushing experiences, becoming a sweet incense to God. “I know your works, your love and faith and service and patience endurance, and that your latter works exceed the first” (Revelation 2:18, 19, RSV).

This commendation is similar to that used for Ephesus, the first stage of the church (Revelation 2:2), but supplemented with “your latter works exceed the first.” Perhaps in the Lord’s estimation the works of Thyatira were even more abundant than the works of Ephesus. Or perhaps that expression means the works of Thyatira near the end of that period exceeded the works done at its beginning. Or perhaps that Jesus valued their patient endurance (mentioned later) even above their charity and service (mentioned earlier). Not that love and faith are less important, but Papal persecutions were so strong, patient endurance was specially difficult and thus more highly appreciated.

At the beginning of Waldo’s ministry as messenge to Thyatira, he was not much of a heretic from the Catholic perspective. He was not unique in taking vows of poverty or in devoting himself to the study of the Scriptures. Both of these things had been regular practices in some monasteries for centuries. Like others of their day, Waldo and the Poor Men of Lyons dressed like Monks, lived in chastity, went barefoot or in sandals, and pooled their earnings.

For a while the clergy did not object to this new group. They were even allowed to read and sing in the churches. But when Waldo and his followers began to preach publicly, the Archbishop of Lyons sharply reminded them that only the bishops were allowed to preach.3

But Waldo and his followers wanted to preach freely. Consequently in 1179 Waldo sought official approval from the Catholic Church. He and his followers wanted to be recognized as a holy order, much like other orders of monks who were not full-fledged priests but who desired nonetheless to live a religious life. So a delegation of Waldenses presented themselves before the Third Lateran Council in order to obtain approval for their movement.

An English friar named Walter Mapes examined Waldo’s small group and wrote this. “We saw Waldensian men in the Roman council held by Pope Alexander the Third. They were simple and unlearned, and were thus called from the name of their founder, Valdo, who was a citizen of Lyons on the Rhone. They presented to the Pope a book written in the old provencal language, in which there were texts and comments of the Psalms, and of many books of the Old and New Testaments. They most urgently requested him to authorize them to preach because they saw themselves as experienced persons, although they were nothing more than dabblers.”

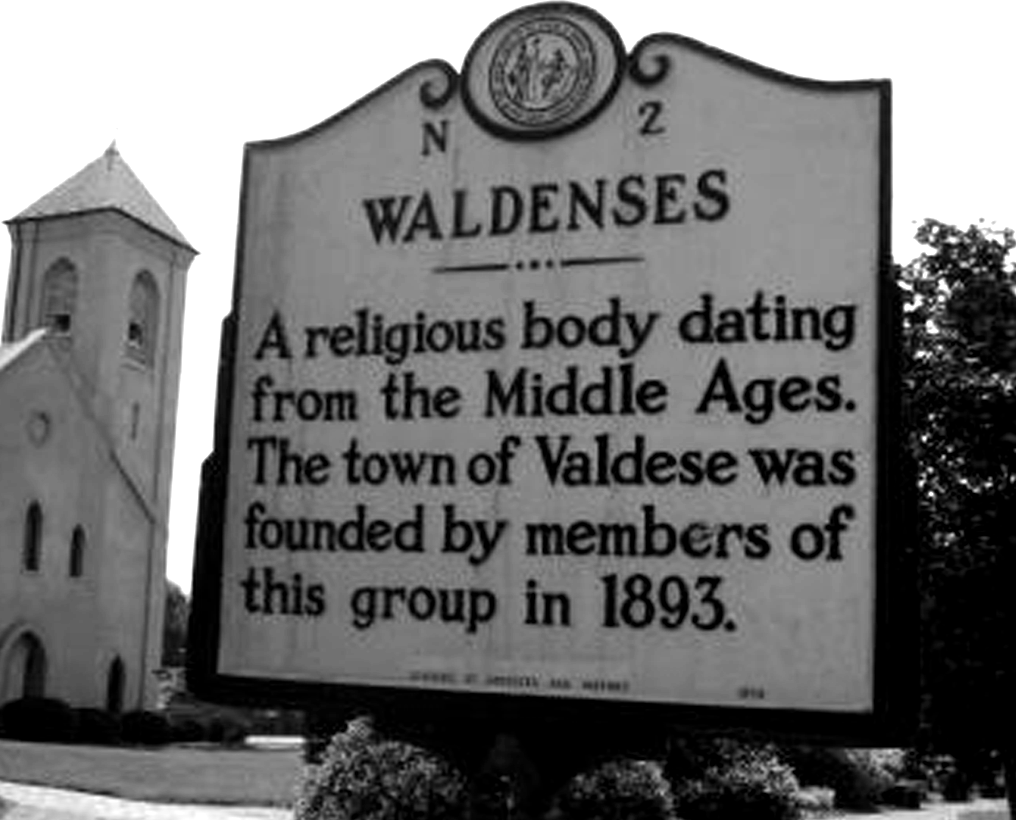

Interesting sign from Valdese, North Carolina

He describes the Waldenses as “having no fixed habitation. They go about two by two, barefoot, clad in woolen garments, owning nothing.” Friar Mapes summed up his opinion of them – “Shall the word be given to the ignorant, whom we know to be incapable of receiving it, much less of giving in their turn, what they have received? Away with this, erase it! Let waters be drawn from the fountain, not from puddles in the streets.”

The Waldenses made a pretty poor impression on the council. As part of their petition, they affirmed their belief in transubstantiation, prayers for the dead, and infant baptism. Waldo also signed a confession of faith affirming his belief in the Trinity, and in the one Church, Catholic, Holy Apostolic and Immaculate, apart from which no one can be saved. From this we see that the early Waldenses considered themselves to be Catholic in all matters of theology.

One might ask if this disqualifies Waldo as the fourth messenger. No, because the doctrinal truths that would separate the wheat from the tares were not yet due. Waldo was by all evidence fully consecrated to the Lord, sacrificed all he had in order to spread the Gospel, and lived his life in harmony with the “present” truth.

Seen in this light, Waldo’s efforts to establish the Poor of Lyons as a Catholic order were commendable and even scriptural inasmuch as it was not yet time to come out of Babylon. His petition was considered and would have probably been granted but for one thing: Waldo’s insistence on the right to publicly preach the Word. Neither the Pope nor the local bishops could tolerate this. So Waldo and his disciples were ordered by the council to stop their public preaching.

They refused. Consequently, Waldo and the Poor Men of Lyons brought upon themselves the wrath of the Archbishop of Lyons. Their defiance of the Mother Church ban against public preaching brought them condemnation as heretics, and expulsion from the Church in 1184.

In these early years they had few doctrinal differences with Rome, even accepting all seven sacraments of the Catholic Church. But after being excommunicated and condemned to hell in the next life, Waldo and his followers reexamined such church teachings through Bible study. Not surprisingly, they found differences and began a slow drift away from Catholic dogma.

In the very early stages of their movement, despite opposition, Waldensian churches and schools of learning flourished and spread from France throughout central Europe. Having scripture in their native tongue gave them great influence among the people. In 1220, the Council of Toulouse, trying to suppress this growth, decreed that no lay folk should possess scriptural books. Shortly after this decree the Inquisition began and the Waldenses, while not the sole targets, did not escape. Thousands were burned at the stake – Church and State cooperating in one of the darkest blots on the record of human history.4

– Bro. Jerry Monette (to be continued)

(1) Bro. Frank Shallieu’s book, The Keys of Revelation, begins Thyatira at 1157, one prophetic time of 360 years before the Reformation date 1517. On page 53, Bro. Shallieu has an extensive footnote giving some evidence for his view that “The Waldensian movement commenced about 1157, not 1170 as is generally recognized … there is … evidence that it began just prior to 1160. … Already in … 1160 they [Waldenses] had increased to such an extent, that they were summoned to Rome before a Synod, and were condemned as obstinate heretics. An item under “Historical Notes” in the Clarendon Press 1886 edition of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales mentions that Waldo wrote The Last Age of the Christian Church in AD 1156.”

(2) These dates are not as firm as we would like. If Waldo’s Christian leadership did emerge by 1157, then his birth as late as 1140 would put his age at only 17 at the time. Some references say Peter Waldo died in 1217 in Bohemia, apparently of natural causes. If he was born in 1140, then he would have been about 77 years of age at his passing. Wikipedia gives a death date of 1218, but cautions “the French historian Thuanus dated his death to the year 1179.”

(3) In the late 1100s, not even priests either preached during the mass or instructed the local flock in the practice of religion. Their main duty, besides collecting taxes in the form of tithes for their local bishop, was the administration of the sacraments and to say the Latin mass.

(4) The Waldenses church of today joined with the Methodists in 1974, as a single synod. It differs very much from its medieval origin, but it is still a reminder and a tribute to the faith and labors of Peter Waldo.