Abraham and Melchizedek

Abraham’s faith is well known. We remember him for his prompt obedience to leave his own country and go to a land God would show him. We remember the promise made upon his father’s death for the blessing of all the families of the earth. God honored him for his faith and readiness to sacrifice his only son.

The perception of these men of faith like Enoch, Noah, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and Joseph is often that of a primitive nomadic tribal people who had little touch with the universal issues of the past or future. However, just the opposite is the case. They were men of the greatest stature, with superior wisdom. Some had skill in engineering, astronomy, mathematics, the natural sciences or generalship and all had a focus on family heritage and customs of Godliness. They have no rivals in contemporary depraved humanity.

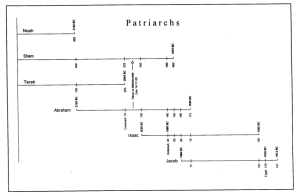

One must look between the lines of the brief Biblical accounts to discover the great principles of those times. After the flood the lives of the patriarchs diminished only gradually. Noah lived to 950. Shem lived to 600 years, just one tenth of human labor under sin. Even Abraham’s father lived more than 200 years. The tribal families began to spread throughout Mesopotamia and mark out their territories. With the Nimrod rebellion, the concept of cities was formed to protect differing cultures and wealth. Rivalry, pride and greed led to alliances and rule over regions and peoples.

One such account is found in Genesis 14. It is a deceptively simple account that hides a profound lesson that has not yet seen its fulfillment. The first nine verses are an account of the first war ever recorded in scripture, which we would not have if the history of Abram and Lot had not been concerned in it. The invaders were four kings, two of them no less than kings of Shinar and Elam (that is, Chaldea and Persia). The invaded were the kings of five cities that lay near together in the plain of Jordan, namely Sodom, Gomorrah, Admah, Zeboiim, and Zoar.

The occasion of this war was the revolt of the five kings from under the rule of Chedorlaomer. Twelve years they served him. The Sodomites were the posterity of Canaan whom Noah had pronounced a servant to Shem. That prophecy was soon to be enforced. In the thirteenth year, beginning to be weary of their subjection, they rebelled, denied their tribute, and attempted to shake off the yoke and retrieve their liberties. In the fourteenth year, after some pause and preparation, Chedorlaomer with his allies set themselves to chastise and reduce the rebels and to fetch his tribute from them on the point of his sword. The four kings laid the neighboring countries waste and enriched themselves with the spoil of the five cities including Sodom and Gomorrah.

Continuing with Genesis 14:10-12 we find: (1) The forces of the king of Sodom and his allies were routed, and many of them who had escaped the sword now perished in the bitumen slime-pits. (2) The cities were plundered. All the goods of Sodom, and particularly their stores and provisions, were carried off by the conquerors. (3) Lot was carried captive. They took Lot among the rest, and his goods.

Here we consider Lot as sharing with his neighbors in this common calamity. Though he was himself a righteous man, and Abram’s brother’s son, yet he was involved with the rest in all this trouble. He was smarting for the foolish choice he made of a settlement here. This is indicated when it is said, “they took Lot, Abram’s brother’s son, who dwelt in Sodom.” So near a relation of Abram should have been a companion and disciple of Abram, and should have abode near his tents. But if he chose to dwell in Sodom, he must thank himself for sharing in Sodom’s calamities. Particular mention is made of their taking Lot’s goods, those goods which had occasioned his contest with Abram and his separation from him.

In Genesis 14:13-16 we have recorded the only account of a military action Abram was engaged in, and this he was aroused to, not by his ambition, but purely by a principle of charity. It was not to enrich himself, but to rescue his nephew. No military expedition was undertaken, prosecuted, and finished, more honorably than this of Abram.

He is here called “Abram the Hebrew,” that is, the son and follower of Heber or Eber, the great grandson of Shem. This may be a reference to Eber’s faith in a degenerating society. Abram acted like a Hebrew – in a manner worthy of the name and character of a religious teacher. This is the first occurrence of the title “Hebrew” in Scripture. The name later came to mean “one from beyond,” either those beyond the Euphrates River or those stateless semi-nomads. That was the condition of Abram, one without a country, but by faith he waited for the promise.

He received news of his kinsman’s distress. The tidings were brought by one who escaped with his life. He was likely a Sodomite, and as such deserved no special recognition. Yet knowing Abram’s relation to Lot and concern for him, he appealed for Abram’s help.

Now Abram prepared for the expedition. The cause was plainly good. His call to engage in it was clear. Therefore he “armed his trained servants,” born in his house, to the number of 318 – a great family, but a small army, about as many as Gideon’s that routed the Midianites (Judges 7:7). He drew on his trained servants, not only instructed in the art of war, but led in the principles of faith. For Abram commanded his household to “keep the way of the Lord” (Genesis 18:19). This shows that Abram was a great man, who had many servants depending upon him, which was not only his strength and honor, but gave him great opportunity for doing good. He was a man who not only served God himself, but instructed all about him in the service of God. As a wise man, and a man of peace, yet he disciplined his servants for war, not knowing on what occasion he might need them.

He prevailed with his neighbors Aner, Eshcol, and Mamre to go along with him. It was his prudence to strengthen his own troops with their auxiliary forces. Probably they saw themselves concerned to cooperate against an imposing power, lest their own turn as subjects should be next.

His courage and conduct were remarkable. What could one family of husbandmen and shepherds do against the armies of four princes, who now came fresh from blood and victory? It was not a vanquished, but a victorious army. “The righteous is bold as a lion.” Abram was no stranger to the stratagems of war. He “divided himself,” as Gideon did his little army (judges 7:16), that he might come upon the enemy from several quarters at once, and so make his few seem like a great many. He made his attack by night, that he might surprise them. His success was remarkable.

He defeated his enemies, and rescued his family. We do not find that he sustained any loss. He rescued his kinsman, Lot. Twice here he is called “his brother.” The relation between them made him disregard their former dispute, in which Lot acted poorly toward Abram. Abram might have justly upbraided Lot for his folly in quarreling with him and removing from him and tell him that he was well enough served. He might have regarded Lot’s plight as properly serving his folly. But Abram takes this opportunity to be magnanimous, to give a proof of his sincerity and reconciliation. “A brother is born for adversity” (Proverbs 17:17).

Abram also rescued the rest of the captives, for Lot’s sake, though they were strangers to him and as such he was under no obligation to them. They were Sodomites, and though he might have recovered Lot alone by a ransom, yet he brought back all the women, and the people, and their goods. As we have opportunity, we must “do good to all men.” Abram’s victory over the kings finds a parallel in the language of Isaiah concerning Cyrus centuries later. Isaiah 41:2, “[The Lord] raised up the righteous man from the east, and made him rule over kings.”

The section of Genesis 14:17-20 begins with the mention of respect from the king of Sodom for Abram at his return from the conquest of the kings. But first is the story of Melchizedek. Who was he? He was “king of Salem” and “priest of the most high God,” who went forth to meet Abram on his return from the pursuit of Chedorlaomer and his allies, who had carried Lot away captive. The meeting is described as having occurred in the “valley of Shaveh, which is the king’s valley.” This is the valley east of Jerusalem through which the Kidron flows, noted in 2 Samuel 18:18. He brought refreshment of bread and wine for the fatigued warriors. After this encounter, he disappears from the sacred writings for a thousand years.

Most expositors regard Melchizedek as a royal title rather than a personal name. This is because in the Hebrew it is always written as two separate hyphenated words: Melchi = King, Zedek = Righteousness or Zadok = Justice.

Recorded in several Qumran fragments (i.e., 11QMelch) and most rabbinical writers concur that Melchizedek was Shem the son of Noah, who was king and priest to those that descended from him. Shem was still living at this moment of history. He may have indeed been the only living patriarch who came from the old world before the flood. Being the oldest living forefather of Abram, there can be little doubt of the bonds of blood and honor that existed between these two noble men.

He was King of Salem, an acknowledged primal name for Jerusalem noted in Psalm 76:2. His domain marked the earliest claim to these sacred regions, long before the Jebusites occupied it, who were in turn evicted by King David. So God established a Semitic king here with a priority over all other religious and ethnic claims to follow.

Melchizedek combined the offices of priest and king. He appeared to Abram as a righteous king who gave peace. He “brought forth bread and wine” for the refreshment of Abram and his soldiers, and in congratulation of their victory. This he did as a king, to honor a victor from the battle. As priest of the most high God he bestowed divine blessing upon Abram. Only a priest could convey God’s blessing and then return the praise to the Almighty.

What did he say? Two things were said by him: (1) He blessed Abram from God: “Blessed be Abram, blessed of the most high God.” Observe the titles he gives to God, which are very glorious. “The most high God” speaks of his absolute perfection, his sovereign dominion over all creatures. He is King of kings. As “Possessor of heaven and earth” he is the rightful owner and sovereign Lord of all creatures, because he made them. This speaks of him as the great God, and greatly to be praised (Psalm 24:1). (2) Melchizedek blessed God for Abram, “blessed be the most high God.” God, as the most high, must have the glory of all our victories. In us he shows himself higher than our enemies (Exodus 18:11), for without him we could do nothing. This is the first record of God intervening to deliver a victory.

What was done for Melchizedek? Abram “gave him tithes of all.” This may be looked upon as an offering vowed and dedicated to the most high God, and therefore put into the hands of Melchizedek his priest. Here is another first. The precedent of the tithe was established long before the Mosaic law and the Levitical priesthood. At this first record of the tithe, God may be marking Shem’s life of 600 years which would be just one tenth of 6000 years of human history. So we should honor those who honor God and those he sanctifies in this drama of humanity.

We note another feature. Paul, in Hebrews 7:4, says the tenth was of the spoils. If Melchizedek was indeed Shem and if Sodom was indeed from the line of Ham and Canaan, as is acknowledged by Jewish sources, then there is a profound lesson here.

We recall the judgment for Ham’s disrespect for his father, Noah. The sons had already been blessed (Genesis 9:1). So the sentence fell upon his son, Canaan. “Blessed be the Lord God of Shem and Canaan shall be his servant” (Genesis 9:26-27). This indicates that the family of Canaan owed the tithe of honor to Shem. But here Sodom rebelled and refused to give tribute. They were in turn overrun by Chedorlaomer, king of Elam. Elam was another son of Shem, however not of the Arphaxad line to Abram. In this peculiar coup, it appears that God forced the tithe from the line of Canaan be given to the line of Shem. Furthermore, while the line of Elam was allowed to compel the servitude, God honored another priority. Because Abram recovered the property and paid homage to Shem, as the “King of Righteousness,” God blessed Abram’s lineage through Arphaxad over the other sons of Shem.

Now we conclude the narrative of Genesis 14:21-24. We have here an account of what passed between Abram and the king of Sodom, who succeeded the one that fell in battle (verse10). This king thought himself obliged to honor Abram, in return for the good services rendered for him. He said, “Give me the souls, and you take the substance.” He pleads for the persons, but as freely bestows the goods on Abram. The king of Sodom had an original possession of both the persons and the goods. But in one sense, Abram’s rescue mission acquired a right to supersede his domain. So to prevent all question, the king of Sodom made this fair proposal. Give back the people. You keep the wealth.

Nevertheless, Abram refused this generous offer. He not only resigned the persons to Sodom’s king, who being delivered out of the hand of their enemies, ought to have served Abram. But he restored all the goods too, except for the tithe rendered to Melchizedek. Even Lot returned to Sodom. Abram would not take from a thread to a shoelace, not the least thing that ever belonged to the king of Sodom or any of his. A lively faith enables a man to look upon the wealth of rebels and villains in this world with a holy contempt. What are all the ornaments and delights of sense to one that has God and heaven ever in his eye?

Abram ratified this resolution with a solemn oath: “I have lifted up my hand to the Lord that I will not take any thing.” Observe here the titles he gave to God, “The most high God, the possessor of heaven and earth.” This is the same expression Melchizedek had just used. His conduct is measured by his benefactor and mentor. We do well to emulate our teachers (2 Timothy 3:14).

This ceremony to “lift up my hand unto the Lord” is first an acknowledgment of God’s sovereignty and absolute truth in our lives. Second, it indicates our vows of allegiance to him alone. So in spiritual matters, swearing falsely has serious consequences. Abram likely vowed before he went to the battle that, if God would give him success, he would deny himself and his own right of taking anything of the spoils.

Abram backed his refusal with a good reason: “Lest thou should say, I have made Abram rich,” which would reflect reproach. Abram now confirmed his refusal with this oath, to prevent any future impugning of his motives. The issue was clear. He had just accepted the promise and covenant of God in the 12th chapter. He was not about to presume against God now by taking to himself the spoils of this earth by his own hand. It was upon the promise and covenant of God that he would depend without the spoils of Sodom. He would not give a premise to the king of Sodom to say that he had enriched Abram.

He finally limits his refusal with a double proviso: (1) The food of his soldiers: they were worthy of their meat while they trod out the corn. (2) A share for his allies and confederates: “Let them take their portion.” Those who are strict in restraining their own liberty ought not to impose restraints upon the liberties of others, nor to judge of them accordingly. We must not make ourselves the standard to measure others. There was no reason why Aner, Eshcol and Mamre should deny their right as Abram should deny his. They did not make the profession that he made, nor were they under the obligation of a vow. They had no covenant prospects as did Abram. By all means, “let them take their portion.”

Now here is an interesting detail. In the 12th chapter God gave Abram the terms of the covenant to leave his own country and go to a land he would show him. Then he gave him the nature of the promise. Now here in the 14th chapter, upon entering the land, Abram demonstrates this great fidelity to his forefathers and benevolence in rescuing Lot. Next, in the 15th chapter, Abram takes five animals and divides this sacrifice in two parts. As the sun went down God’s acceptance was shown in “a smoking furnace and a burning flame that passed between the pieces.” Only then in Genesis 15:18 it is said: “In the same day the Lord made a covenant with Abram.”

We notice that there were three conditions for the covenant in chapter 12. (1) To leave his country, (2) to leave his kindred, and (3) to leave his father’s house. A similar call comes to Abram’s seed to separate themselves from all associations that would obstruct their faith. Abram left his country, Ur of the Chaldees, with all its status and earthly prestige. He left his father’s house, with the protection, customs and traditions of family when he departed from Haran at Terah’s death. But only in the 14th chapter does he demonstrate a final separation from his kindred. Lot’s loyalties are then filly separated from Abram’s loyalties. He chose the family of God over the riches of his natural family. Abram yielded all honor to Melchizedek and laid the foundation for God q accept his sacrifice and confirm the covenant.

Now among all the Hebrew scriptures, only a Psalm of David picks up the name of Melchizedek in this shred of ancient history (Psalm 110:1-5). David’s forecast of Messiah adds the subtle phrase that the order of Melchizedek is “forever,” or as the Hebrew indicates Owlam: “time immemorial,” from antiquity to eternity, a perpetual priesthood.

The Apostle Paul engages this noble theme in Hebrews chapters 5, 6 and 7. Paul’s great treatise is addressed to Jews familiar with the Holy Scriptures and those who trusted in the Levitical or Aaronic priesthood. His point is that the divine arrangement recognizes only the Aaronic and Melchizedek priests. There may have been an unrecorded challenge to Jesus qualifying as a priest because he was not of the Levitical family but of Judah.

Paul develops his reasoning that the Melchizedek priesthood preceded and was superior to that of Levi. He also shows that this priesthood was distinctly different. He first reminds them that the Levitical priests were appointed for sacrifice for sins, but not Melchizedek. Then he appeals to David’s Psalm which declares that Messiah would be of the Melchizedek priesthood. The reason for this is that it combined the office of King and Priest. Furthermore, this was a blessing priesthood and not a sacrificing priesthood (Hebrews 7:12-17, 24-25).

In Hebrews 6:20 Paul also picks up on the single word “forever” in Psalms. “Jesus, made a high priest forever after the order of Melchiôedek.” He explains-in 7:3 that he was “without father, mother, without descent, neither having beginning of days, nor end of life.” This has led to some speculations that Melchiôedek, Enoch and others never died.

Melchizedek’s genealogy was not in the records of the Gentiles. The creation tablets and the Genesis records were carried into the new world by Noah. Then new family records were formed among the various nations. Shem would not be recorded in those birth and death records of other nations originating after the flood. For those living in Abraham’s day, the account of this King Melchizedek’s mother or father would be recorded in none of those books, but might be known only to those of Shem’s direct lineage who kept those earliest sacred accounts. Later these would be conveyed to Moses. Even the early Babylonian cuneiform Epic of Gilgamish records Noah as “the immortal one” because they had not the records of his lineage.

However, the point Paul makes is that Melchiôedek did not claim the throne because of ancestors or genealogy. He owed it to God’s own appointment. And of course the title had no predecessor either. Just so, Jesus did not become Messiah because of human genealogy or inheritance, nor even from the tribe of Levi, but by divine appointment. Furthermore, his priesthood is perpetual and will extend to the Messianic age of blessing all the families of the earth.

Now Paul develops the point in Hebrews 7:4-10 that the Levitical priesthood is subservient to that of Melchizedek and will be replaced. As Melchizedek was superior to Abram, so Christ is superior to Aaron. He shows this in that not only father Abraham paid tithes to Melchiôedek, but also all the Levites in Abraham’s loins, who were accustomed to receiving tithes, where really themselves paying tithes to Melchizedek. Because they considered themselves children of Abraham, they must recognize the greater priesthood which Abraham tithed.

In addition he directs their attention to the role of sacrificing Levitical priests for the sins of the people. This must be followed with the results of the sacrifice, from a blessing priesthood. This will be the work of the Millennial Melchizedek priesthood, of which Jesus is now the head. Even Aaron, when finishing his work of sacrificing, must change to glory garments in order to bless the people. Just so, this royal priesthood will no longer wear the robes of sacrifice but of glory and honor. Theirs will be the honor of dispensing the blessed results of the age of sacrifice.

The work of the Jewish Age was to take out a typical people, Israel after the flesh. The work of the Gospel Age has been to gather the Elect, “a people for his name,” as antitypical priests like Aaron, to finish the work of sacrifice. The future work of the Melchizedek priests is to dispense the blessings to all the families of the earth, conferred through the Abrahamic promise, through the New Covenant. This will be the “good tidings of great joy, which shall be unto all people.” Even now the Melchizedek head is in power and glory. During this overlapping of the ages, many body members are already joined with him, while those who are “alive and remain” are finishing the sacrificing work of the Aaronic priesthood.

But Paul was not the only one who caught this noble theme of a reigning priesthood. So did Peter in 1 Peter 2:5. “Ye are a chosen generation, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a peculiar people.” This could not be said of the Levitical priesthood.

John also recognized this unique appointment in writing Revelation 1:6, “[Jesus Christ] hath made us kings and priests unto God and his Father; to him be glory and dominion for ever and ever.” Then in Revelation 5:10 he writes: “Thou hast made them into a kingdom and priests for our God, and they will reign over the earth.” (Fenton)

These will be those spoken of by the prophet, Isaiah 32:1, “Behold, a king shall reign in righteousness and princes shall rule in judgment.” And also Isaiah 9:6-7, “The government shall be upon his shoulder and his name shall be called Wonderful, Counselor, the Mighty God, the Everlasting Father, the Prince of Peace. Of the increase of his government and peace there shall be no end, upon the throne of David and upon his kingdom, to order it, and to establish it with judgment and with justice from henceforth even forever. The zeal of the LORD of hosts will perform this.”

Then the story of Abraham and Melchizedek will be complete.

-Jerry Leslie