“Here I Stand”

The Reformation and its Aftermath

In Germany, Wittenberg’s nobility still took Medieval pride in their collection of relics from the saints. Fittingly, these were set off in gold and silver artwork and — to maintain the mystery — viewing was permitted only during the great feast day of “All Saints.” A small admission fee permitted the faithful to view “a fragment of Noah’s ark, some soot from the furnace of the Three Children, a piece of wood from the cradle of Jesus Christ, some hair from the beard of St. Christopher, and nineteen thousand other relics of greater or less value.”1

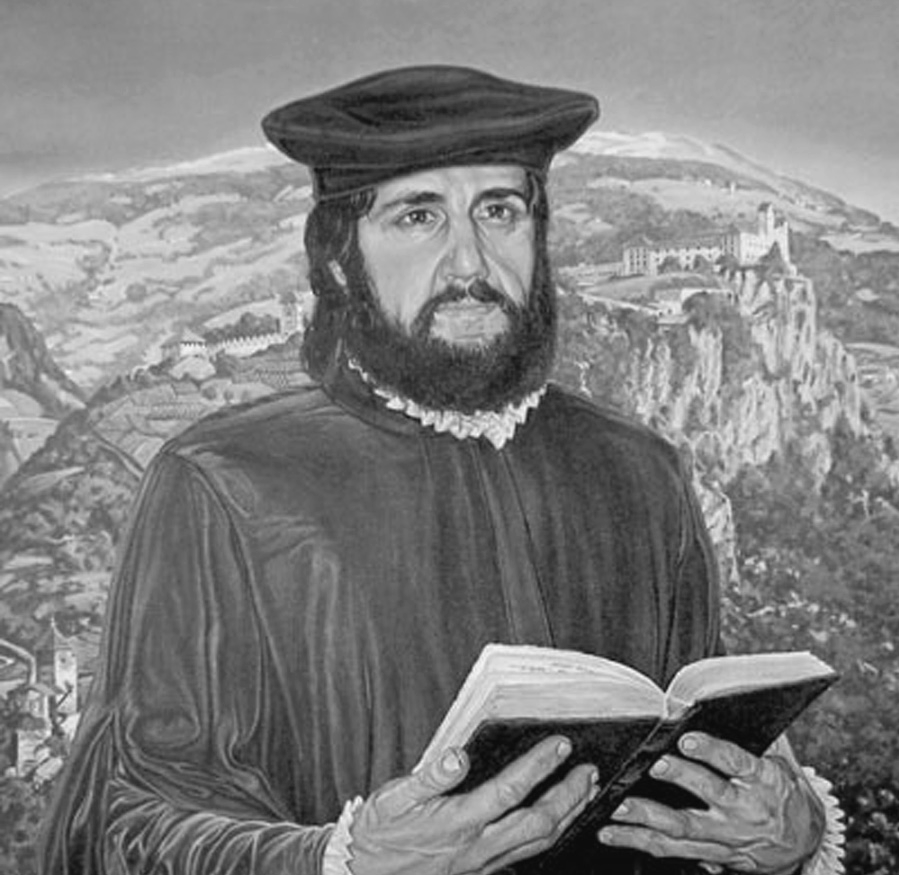

Midday on October 31, 1517, the day preceding “All Saints,” a tonsured Augustinian monk who served as the theology professor at the local university made his way to the church door of Wittenberg castle. There he posted a handwritten document in Latin entitled a “Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences.” The “disputation” set forth 95 theses challenging the theology of selling “indulgences” or the church’s guarantee of deliverance from sin. Martin Luther was certain that this was bad Catholic theology. If a person was literate, they were literate in Latin, so Luther’s challenge was read and devoured with great interest. The literate then translated it for the benefit of bystanders.

Soon the wheels of ecclesiastical discipline began their slow inexorable movement to grind up this most recent challenger. But, the world was changing. Not even seventy years earlier Johannes Guttenberg’s printing press had opened the era of mass communication. For papacy, the time-tested methods for dealing with dissent were to prove unworkable. Within two weeks, copies of the 95 theses were posted all over Germany, within five weeks they arrived at the Vatican. An emerging literate middle class could no longer be controlled by superstition.

As events would unfold, compromise and reconciliation with Rome would prove to be impossible. The scriptural testimony that “the just shall live by faith” (Romans 1:17) was to make a deeper and deeper impact on Luther’s belief. Luther was to prove to be remarkable for his morally courageous, articulate, energetic, and unwavering stand for principle in opposition to Rome.

At his trial in Worms on April 17, 1521 Luther, speaking first in German, rather than Latin, stunned the audience by his closing statement: “Unless I am convicted by scripture and plain reason, I do not accept the authority of popes and councils, for they have contradicted each other — my conscience is captive to the word of God. I cannot and I will not recant anything, for to go against conscience is neither right nor safe. Here I stand. God help me. Amen.”

Noblemen, risking their titles, lands, and lives would soon protect, hide, and actively aid Luther in advancing the cause of “Protestantism.” What began with an obscure professor’s challenge to indulgences ended by changing the face of Europe.

THE ANABAPTISTS

Soon, blood was everywhere. Warfare, pestilence, and poverty became the rule of life. Fearsome executions awaited any, Catholic, Protestant, Anabaptist, and frequently Jew, who would not conform to the convictions of the local majority. Starting from that fateful day in Wittenberg, 131 years of unrelieved misery reigned in Europe. At long last the Peace of Westphalia (1648) set the modern map of Europe with Catholics and Protestants agreeing to an uneasy truce.

With the broader warfare ended, a full generation of fighting continued within national borders to establish conformity to state worship, be it Protestant or Catholic. John Milton’s (1655) poignant elegy mourned the recent, brutal, and horrific Catholic massacre of the followers of Peter Waldo:

“AVENGE, O Lord, thy slaughtered Saints, whose bones

Lie scattered on the Alpine mountains cold;

Even them who kept thy truth so pure of old …

Their martyred blood and ashes sow …

That from these may grow a hundredfold, who …

Early may fly the Babylonian woe.”

The Reformation led to church ransacking and consigning images and reliquaries to flame. Church lands were confiscated. In Protestant lands monasteries and convents were emptied. Like Luther himself, many of their former celibate inmates married and raised families. Luther’s marriage to Katharina von Bora, a former nun, left pious adherents of Catholicism mortified.

Though Protestant churches now stood with stark interiors, they were more alive than ever. Christ was now the one mediator between God and man. The sermon, rather than the mass, now served as the focal point for the church service. Luther believed that “the Devil, the originator of sorrowful anxieties and restless troubles, flees before the sound of music almost as much as before the word of God.” In unison, it was the congregation that now sang the modern and soul-inspiring hymns, including Luther’s chorale, “A mighty fortress is our God.”

The presses continued their labors. Soon tracts and Bible texts were placed directly into the hands of a thoughtful and increasingly literate citizenry. Wherever Protestantism went, groups emerged earnest to learn only from scripture, without appealing to church authority. This “grass roots” religious movement soon proved unwilling to stop the reforming where Luther did.

Anabaptists were wide-ranging in doctrine, but three issues characterized them. They took exception to church- state union, considering it whoredom. They broke with Luther and Ulrich Zwingli on infant baptism. For Anabaptists, baptism was for those who had: “Received Jesus Christ and wished to have him for Lord, King and Bridegroom, and bind themselves also publicly to him, and in truth submit themselves to him and betroth themselves to him through the covenant of baptism and also give themselves over to him dead and crucified and hence to be at all times subject, in utter zeal, to his will and pleasure” (The Ordinance of God, Melchior Hofmann, 1530).

“Here I stand, I can do no other, God help me, Amen.”

A third point of contention was Luther’s support for the mass. Here the Anabaptists, Zwingli, and other reformers argued that Christ intended the bread and the wine as symbols, a remembrance, a memorial, and not as a sacrifice. Meeting with Zwingli to dialogue on the mass, Luther moved to the chalkboard writing only, “This is my body.” In his passionate and irascible manner, the force of this effort broke the chalk. For Luther the discussion was ended. Though he disagreed with the Catholic church on transubstantiation, he affirmed the “real presence” of Christ in the mass explaining his position:

“I have often enough asserted that I do not argue whether the wine remains or not. It is enough for me that Christ’s blood is present; let it be with the wine as God wills. Sooner than have mere wine with the fanatics, I would agree with the pope that there is only blood” (Confession Concerning Christ’s Supper, 1528).

The Anabaptists focused on Bible study, prophecy, and also studied the tabernacle. Some Anabaptist fellowships in northern Italy, Poland, and Romania even denied the trinity. Nearly one hundred years later, writing on the eve of the thirty years war, one of their highest tributes comes from an implacable enemy:

“Among all the heretical sects which have their origin from Luther … not a one has a better appearance and greater external holiness than the Anabaptists. Other sects are for the most part riotous, bloodthirsty, and given over to carnal lusts; not so the Anabaptists. They call each other brothers and sisters; they use no profanity nor unkind language; they use no weapons of defense … they own nothing in private but have everything in common. They do not go to law before judicial courts but bear everything patiently, as they say, in the Holy Spirit. Who should suppose that under this sheep’s clothing only ravening wolves are hidden?” (Of the Cursed Beginnings of the Anabaptists, Christoph Fischer, 1615).

Accounts of the Reformation such as of Merle d’Aubigné cited earlier (and in The Time is at Hand, page 346), focus on fringe groups of Anabaptists and have not a kind word to say. Current historians have criticized the persecutors of these dear brethren.2 In a comment upon Zwingli’s essay, “Refutation of Baptist Tricks,” the editor writes:3

“In this paper Zwingli show’s himself up in a very bad light. This is no place in which to describe the outrageous treatment which the Anabaptist party received in Zurich and elsewhere through Switzerland. The author feels the freer to use such a term because he is not himself a Baptist, but he comes to the subject merely as a historical student.

… The part which Zwingli played in this wretched business is a serious blot upon his reputation. The Baptists were pursued relentlessly; drowning, beheading, burning at the stake, confiscation of property, exile, fines, and other forms of social obloquy were employed to suppress them The fact shows plainly that the persecuting spirit in the times of the Reformation was just as rife among Protestants as among Roman Catholics, and that the devil was abroad in the hearts of those who considered themselves on both sides as the true servants of the Lord Jesus Christ.”

In the 21st century, the heritage we owe the Anabaptists has not only been reclaimed, but recognized as one of the most significant developments of the Reformation. A current BBC history divides the reformers protesting the Catholic church into two camps — on one side, Luther and Zwingli who saw Christianity encompassing the whole of society. These wished for Christians to control the reigns of political power. On the other side, the Anabaptists who saw the separation of church and state as essential.4

QUAKER AND HUGUENOT TESTIMONY

“Bear the cross, and stand faithful to God, then he will give thee an everlasting crown of glory, that shall not be taken from thee. There is no other way that shall prosper than that which holy men of old have walked” (Thomas Loe, Quaker, 1662).

Loe’s preaching in Oxford moved young William Penn to openly criticize the Church of England, leading to Penn’s expulsion from Oxford University. Penn, the son of a British Admiral, left for France and soon found his way to L’Academie Protestante de Saumur, a center for Huguenot Protestant learning that briefly flourished in France. This was a consequence of liberal policies in 1598 instituted by the Protestant born and raised Henry IV. Henry wished to make amends for the horrors his predecessor, Charles IX, perpetrated in the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre (1572). Conditions in the world were changing. Though atrocities would follow, a new consciousness was emerging. Huguenots later would be expelled from France (1685), but tearing out heretic’s tongues, nailing them to carts, burning them, drowning them, massacring them, were losing favor as accepted instruments of statecraft.

The air at Saumur was filled with discussion of the prophecies in Daniel and Revelation. Collective opinion held that the churches of Revelation were progressive and that the church was in the sixth, or Philadelphia stage. This point was not lost on Penn later in his life. Huguenot scholar Pierre de Launay (1573-1661) sought to determine when, during the Gothic and Vandal ravages of Rome, it was proper to begin counting the 1260 days of Daniel using the day-for-a-year formula. By far, the most significant scholar of this period was Pierre Jurieu (1637-1713). Writing after the Huguenot expulsion from France in 1686, Jurieu would extend de Launay’s methods, concluding that the Lord’s special judgment would fall on France — the tenth part of the city of Revelation 11:13 — in the decade of 1780-90, and certainly by 1796.

Returning to England, Penn found himself among the Quakers and soon he was arrested for running afoul of the religious laws. The seriousness of the charges kept escalating and eventually his treatise “The Sandy Foundation Shaken” (1668) put him in the Tower of London, the bishop charging blasphemy. Penn had criticized Trinitarian belief as unscriptural and illogical. “[For] what can any man of sense conclude but that here be three distinct infinites” and, “It is manifest then, though I deny the Trinity of Separate Persons in one Godhead, yet consequentially, I do not deny the deity of Jesus Christ.”

CROSS AND CROWN

Penn’s seven months in the tower were spent writing “No Cross-No Crown,” a widely disseminated treatise that fixed the image of the Cross and Crown in the hearts and minds of the Lord’s people from that time forward. Penn’s words are simple, sincere, and scriptural: “What is our cup and cross that we should drink and suffer? They are the denial and offering up of ourselves, by the same spirit, to do or suffer the will of God for His service and glory, which is the true life and obedience of the cross of Jesus” (Chapter 4, Section 4).

Penn reexamined scriptural promises passed over since St. Augustine. Theologians had minimized the importance of the church’s life experiences — Augustine considering these but memories “dissipated like clouds.” Penn recognized that life experiences acquired under unfavorable conditions would be an eternal benefit.

The death of Sir William Penn in 1670 left young Penn in control of the family fortune, including a massive debt owed to his father by the crown. With this financial support, Penn now had the means to pursue his pilgrim ministry nearly full time. He traveled throughout England, Ireland, and along the Rhine River preaching the Quaker doctrine. Recognizing that the crown could never remit the growing debt to his late father, he asked for a colony in payment. His focus on this “holy experiment” of founding Sylvania (the woods), and planning and building its principle city of Philadelphia, would be his best- remembered legacy. Echoes of Saumur ring in the name Philadelphia. When the council approved his request, they insisted his father be honored, and changed the colony name to Pennsylvania.

Statue of William Penn

In practical politics William Penn proved highly capable as a lawgiver, mediator, and practical pacifist. On North American soil, his bold unarmed approach to the native-Americans chiefs at the great elm of Shakamaxon caused them to set down their bows and arrows. Penn’s governance became legendary. Long after his passing; there still was talk of the Indians’ deep mourning over the death of their dear brother to whom they had bound themselves “to live in love.” Voltaire, who usually could manage only derisive comments about religion, praised Penn as the greatest lawgiver since Moses. Though the revolution to follow would not be by pacifist means, Penn’s hopes were that God would make his colony “the seed of the nation.” And so it would prove.

With the religious wars of Europe ended, the following century was one of explosive growth on every front of human inquiry. It was now understood that the earth revolved around the sun, the orbit of the moon was explained, light was explained, and mechanical engines were developed to replace the muscle-power of draught animals. Perplexing math problems unsolved for thousands of years were solved. New musical forms opened unexplored realms for the human spirit. The social well-being of common people became the focus of interest for new sciences seeking to understand social, political, and economic theory. All of this fed the minds of people about a revolution in the social and political order. Importantly, this all impacted religion. With an eye to the recent past, there was a suspicion of all things religious. Agnosticism, deism, and Unitarianism became the preferred expressions of spirituality among society’s leaders.

FRANCE AND PHILADELPHIA — 1776-1799

While France was the focal point for much of this effort, it would be pamphlets from France that were to fan the embers of revolution in the American colonies. Following a declaration of independence originating from Philadelphia on July 4, 1776, the American colonies broke from England after five years of fighting. Seizing on this example the revolution came home to France. Heeding cries of “Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity,” it was the common citizens who led a bloody revolution serving notice to monarchs everywhere that their days were numbered. Significantly, reverses occurred. The French revolution also led to the rise of Napoleon.

Napoleon represents a decisive watershed in world history. The world had never before seen anyone quite like him. Like Alexander the Great, Napoleon had a vision not only for conquest, but for remaking the culture of Euope. The pope’s cooperation with the Allies against the French Republic, and the murder of the French attaché, Basseville, at Rome, led to Napoleon’s attack on the Papal States. Attempting to export revolution to Rome, the French General Duphot was shot and killed. In response, the French took Rome February 10, 1798. Because the pope refused to submit, he was forcibly taken from Rome on the night of February 20, and brought first to Siena and then to Florence. At the end of March, 1799, though seriously ill, Pius VI was hurried over the Alps. Finally reaching Valence, he succumbed to his sufferings and died.

Felix Manz, Anabaptist Martyr

Entering into a concordant with Pius VII, elected as successor to Pius VI, Napoleon tersely laid out his terms: “For the pope’s purposes I am the new Charlemagne … I expect the pope to accommodate his conduct to my requirements. If he behaves well, I shall make no outward changes; if not, I shall reduce him to the status of Bishop of Rome” (Napoleon, to Pope Pius VII, 1799).

The refusal of Pius VII to acquiesce sufficiently resulted in 14 years of house arrest and his removal from Italy to Fontainebleau. After Napoleon’s fall Pius would return to Rome in 1814, but this triumph would prove hollow. For the rest of the century the papacy would see only an unremitting loss of prestige, power, and properties.

None of these epoch-defining events were lost on John Lathrop (1731-1820), a Yale-educated divinity scholar. Lathrop was particularly active in drawing attention back to the prophetic studies of Jurieu who had predicted the French revolution over one hundred years before the event. Lathrop’s work recognized the critical importance of Biblical chronology. Soon, William Miller (1824-1863) and others would bring out additional pearls long hidden.

Across a wide ocean, one month before a French mob burned the Bastille (July 14, 1789), Representative John Adams of the United States looked out from his office in Philadelphia, the first seat of government. Adams knew that the power of religion could be exercised for good or ill. In general, his belief was that it had been exercised for ill, and he strongly supported the separation of church and state. As soon as the constitution for the new nation was ratified (1788), it was immediately criticized as incomplete because it failed to define the human rights protected. The agreement was to draft a “Bill of Rights” to correct this. The opening phrase of the first of ten amendments ratified December 15, 1791 marks a turning point for church and state. For the first time in any nation’s history, freedom of worship was official state policy: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

It had been 265 years since Felix Manz, the first Anabaptist martyr, perished in the “third baptism” under the freezing waters of the Limmat River near Wellenberg, Switzerland. At last the Anabaptist entreaty for the separation of church and state was law. As the 19th century dawned, a culture in Europe and North America holding religious, social, political, and scientific world-views unimagined by Luther held world stage. This fulfills Christ’s promise to the church of Philadelphia, “I have set before thee an open door, and no man can shut it” (Revelation 3:8). In the next century, economic upheaval from a movement soon to be called the “industrial revolution,” and scientific advances, would provide Christianity with its greatest challenges and its greatest triumphs.

— Revised from “The Reformation and Martin Luther,”

Herald Magazine, Special History Issue, 2003

(1) d’Aubigné, Merle, History of the Reformation of the Sixteenth Century, (1861-1862), Book 1, Chapter 3.

(2) d’Aubigné, op. cit., Book 11, Chapter 10.

(3) Jackson, Samuel Macauley, Ulrich Zwingli (1484-1531) Selected Works, Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia (1972), page 125.

(4) Naphy, William G., The Protestant Revolution, BBC Books (2007), page 49.