Hebrew “Roots” in Strong’s Concordance

One of the great blessings contributing to an improved understanding of the Bible for non-speakers of Hebrew and Greek was the first printing of the James Strong’s Concordance in 1894. A little assistance in understanding Strong’s references to Hebrew words may be of help since the language structure is so different from English and Romance languages.

Consider the Hebrew word “to write” (Strong 3789). “To write” consists of three letters k-t-b and the dictionary notes that it is a “primary root.” When first starting out it does help to know something about the overall structure and shape of the Hebrew language, for like other Semitic Languages, Hebrew is based on what is normally called a “consonantal root system.”

What this means is that almost every word in the language is ultimately derived from one or another “root” (usually a verb) that represents a general, and often quite neutral, concept of an action or state of being. Usually this root consists of three letters. By making changes to these letters, the original root concept is refined and altered.

There are many ways to make these changes: letters are added to the beginning of the root or tacked on at the end; the vowels between the consonants of the root are changed; extra consonants are inserted into the middle of the root; syllables are appended to the end. Each of these changes produces a new word – and a new meaning. Meanings seem literally to grow out of the root like branches of a tree. But the original, basic idea of the root persists, in one way or another. As we shall soon see, “roots” are then adapted to modern speech and can express ideas never found in the Bible such as building off this root to form the word “typewriter.”

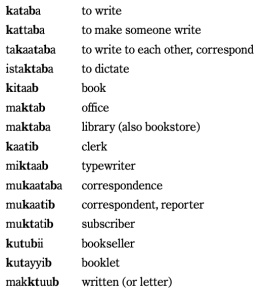

It is easier to see this by taking this specific example and showing what has grown off this root over time, the following examples come from modern Arabic.{1} Since Hebrew and Arabic are close sister languages, this is a completely reasonable comparison. The three consonants, k, t, and b – combined in that order: k-t-b – do of course also connote the idea of writing in Arabic. The simplest word based on those letters is kataba, which means “to write.” That is the root. If you go to an Arabic dictionary and look up the root kataba, you will find, among many other entries, the following (the three letters of the root are printed in bold type so that they stand out).

Baruch, a scribe serving Jeremiah

The connection of all these words with the underlying idea of writing is clear in context, but often is less obvious if you did not know the “root.” Once you read it, you see the connection you might not have noticed on your own. Now take another look at the list of k-t-b words. Apart from the fact that the sequence k-t-b appears in every word, you can also notice certain kinds of changes that might easily be seen as patterns that could be repeated with other roots.

To show what happens, let us see what the prefix of “m” with a vowel means if we take a completely different root and see how this works. For this example let us examine the root d-r-s (Strong 1875). Once again, this is a simple verb described in Strong’s as a “primary root.” It means to “follow” but by implication, “to seek, to ask.” In Arabic the meaning of d-r-s (the verb is darasa) is the same and it is rendered, “to study.” We can now see the connection when we look at Strong 4097, “midrash,” meaning “an investigation,” and we can now see why the Strong’s dictionary references the Strong 1875 root. In English newspapers, we have now become familiar with the Arabic word for schools “madrasa” where the word “madras” has come to mean a school that focuses on the study of the Koran.

We could follow the rules for building off of the roots for all the other words on the list, but it should be remembered that most native speakers of the language do not think about the system in this kind of clinical way, any more than speakers of Romance Languages think about how their tongues are related to Latin or any more than English speakers think about the difference between “strong” and “weak” verbs. It is an instinctive process for the native speakers of Semitic language. But for foreigners learning the language it is important to know that when they embark on understanding Hebrew that they are studying a language the key to which lies in its underlying structure of three-consonant roots.

– Richard Doctor

(1) Adapted from Nicholas Awde and P. Samano, The Arabic Alphabet – How to Read and Write it, Lyle Stuart, Kensington Publishing Co., New York (1986) page 15.