Memorial Observances

“Purge out therefore the old leaven, that ye may be a new lump, as ye are unleavened. For even Christ our Passover is sacrificed for us” (Corinthians 5:7).

FOUR QUESTIONS

Considerations about the Memorial observance were treated in February 1996, when four questions were answered.1

(1) Since Bible Students link the celebration of Memorial to the Passover observance and use the Jewish calendar to determine the date for the 14th of Nisan, why does our Memorial occur consistently two days before the Passover?

(2) Did our Lord’s death on the cross occur at the full of the moon, and if so, what is the spiritual significance of this?

(3) Should not the occurrence of the full moon dictate the proper date for the celebration of the Memorial Supper, especially in view of the significance of Jesus’ death occurring at that time?

(4) When our Lord died on the cross at full moon, was there also an eclipse of the moon? If so, what would this illustrate and does it help establish the date of the crucifixion?

Here we build upon that work by addressing four additional questions.

Question Five

How Do the Temple Festivals Relate to the Memorial?

The cycle of Temple festivals provided much of the joyful anticipation for the Lord’s people under the Law Covenant that we enjoy today in our regular conventions. The Temple festivals appropriately open in the spring of the year with “the Passover” (Pesach in Hebrew) that links directly to the Feast of Unleavened Bread.

Another Temple Festival, the Feast of Booths, is a convenient antipode that consists of a week-long autumn harvest festival. The Feast of Tabernacles was the final and most important holiday of the year, described as “a lasting ordinance.” The divine pronouncement “I am the Lord your God” concludes this section on the holidays of the seventh month.

The Feast of Tabernacles begins five days after Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement on the fifteenth of Tishri (September or October). That feast is a drastic change from one of the most solemn holidays in the Jewish year to one of the most joyous. However, whereas Jesus did establish an antitype of the Passover and asked us to remember and observe his death, he said nothing respecting the Feast of Booths. This may suggest that its antitype points to the Kingdom (Tabernacle Shadows, page 93).

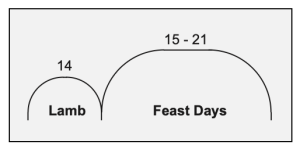

The Passover refers to the sacrifice of the lamb, not to the eating of the lamb, which was to be attended with unleavened bread. Thus keeping “Passover” was something on the 14th day, and eating the Passover was something on the 15th day, the first day of the “feast.” Hence, the Feast of Unleavened Bread, properly speaking, is distinct,2 as we can see from Leviticus 23:5,6, Numbers 28:16,17, 2 Chronicles 30:15,21, Ezra 6:19,22, Mark 14:1.

The “Passover” takes place on the 14th of Nisan. The “Feast of Unleavened Bread” commences on the 15th and lasts seven days to the 21st of the month (Exodus 12:15). But from their close connection they are generally treated as one, both in the Old and New Testament (Matthew 26:17, Mark 14:12, Luke 22:1). Josephus describes it as “a feast for eight days” of unleavened bread (Antiquities 2.15.1).

Question Six

What were the most significant changes introduced after the Babylonian exile that were observed in our Lord’s day?

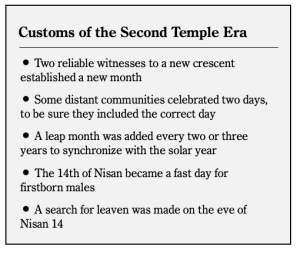

Before our Lord’s day, during the period of the Second Temple (built between 519 and 515 BC), and for three centuries after its destruction, a council of the Sanhedrin decreed when the new months began. The start of each month was established by observing the arrival of the new moon. The council would meet on the thirtieth day of the month to hear the testimony of “two trustworthy witnesses” as to whether they observed the new crescent moon on that day. If they had, that day was declared the first of the new month. If they did not, then the next day was declared the first of the new month.

Once the council made their declaration, the new month was announced by fire signals to inform the communities outside of Jerusalem. Distant villages which could not always receive prompt notice celebrated the new moon for two days to be sure they included the correct day. Some holidays were also celebrated for two days due to the uncertainty of the new moon.

The council compensated for solar and lunar differences by adding a “leap month” in the calendar every second or third year as the eleven-day difference between a solar year, and 12 new moon periods, accumulated. The Jewish reckoning allowed for some flexibility, considering astronomical facts as well as religious and agricultural requirements. They observed the state of the crops and the need to avoid muddy roads on the Passover journey, and inserted the leap month in an advantageous way.

During this period the customs of the festival were shifted to include much of what is still considered proper celebration, but these ceremonial refinements did not alter the main activities of the 14th and 15th day of Nisan. On this there is an almost “unanimous opinion of Jewish scholars.” 3

Most significant, the 14th day of the first month after the Babylonian exile was now designated as a “fast” day for all the male firstborn of Israel. The events are described by a Jewish website:4

“The Fast of the Firstborn. On the day before Pesach, the 14th Nisan, it is necessary for firstborn sons to fast. Called Ta’anit Bechorim, this fast commemorates the deliverance of the first born Israelites in Egypt (Exodus 12: 23, 24). It is usual for the firstborn to attend morning service and to participate in a Siyyum, a religious celebration that marks the completion of a volume of the Talmud or any rabbinic work. In Jewish teaching, study is an act of religious joy and the participant is thus absolved from this very minor fast and able to partake of refreshment.

“The Search for Chametz. On the eve of the 14th day, a search is made for leaven throughout the home. This is called Bedikat Chametz. After the search, the leaven is set aside to be burned on the following morning. It is customary to place a few pieces of bread in various parts of the house so that the search is not in vain. It is, however, not right to collect only these pieces without making a search throughout the home.”

Hence, while the New Testament accounts are correct, there has been confusion among some Bible commentators who look at the instructions in Exodus without recognizing that there were differences between the observances of the Passover festival as directed in Exodus, and prevailing Jewish custom after the Babylonian exile as practiced for more than 500 years by our Lord’s day. These issues were compounded by differences between the Roman and Jewish “day.” Observant Jews reckoned the start of each day near sunset, and the prevailing Roman custom we have inherited began the day at midnight.

Earlier in this publication, the harmony of the Gospel accounts with the calendar date of Friday, April 3rd, 33 AD as the date of the Lord’s crucifixion and burial has been discussed in the article “Dating the Crucifixion.” 5 The Last Supper in the upper room would be on the preceding Thursday night by our reckoning.

Question Seven

What is the record of the primitive Church observance of the 14th of Nisan?

Any undertaking to change the date of the Memorial must be viewed with deepest concern in consideration of the special warning in Daniel 7:25. The scriptural record is clear that our Lord suffered and died on a Friday and that he rose again early in the morning on Sunday. Since the church came to recognize that Sunday, rather than the Sabbath, as the appropriate day for worship, there was also a desire to see every Passover follow this same pattern. This would not be possible without changing the manner of manner of calculating the dates.

However, historical records show that our observance is in conformance with primitive church custom for calculating the Passover. Pastor Russell treats the changes coming into the primitive worship in Studies in the Scriptures, Volume Six, “Passover-Easter,” pages 481-484. See also the treatment in Foregleams of the Messiah.6

One of the curious footnotes in the history of the divergence of the English church from the Church of Rome may be found in the English church’s treasured history by the “venerable” Bede completed in 731 AD. His writings suggest that the English people kept a corporate historical memory that never quite forgot their setting aside custom received from Apostolic times so that they could be accepted into fellowship with the church of Rome, and that what he calls “Easter” was not always celebrated on a Sunday.

By way of background, during the political and economic collapse of the Western Roman Empire, Roman settlement in London was abandoned in 409 AD. After nearly two centuries of no contact, formal contact was reestablished by a formal visit in 603 AD from Bishop Augustine acting on behalf of the Roman Church.7 Up until the 600s, Brtions celebrated our Lord’s death and resurrection following the same scriptural formula that we use. Bede writes as follows.8

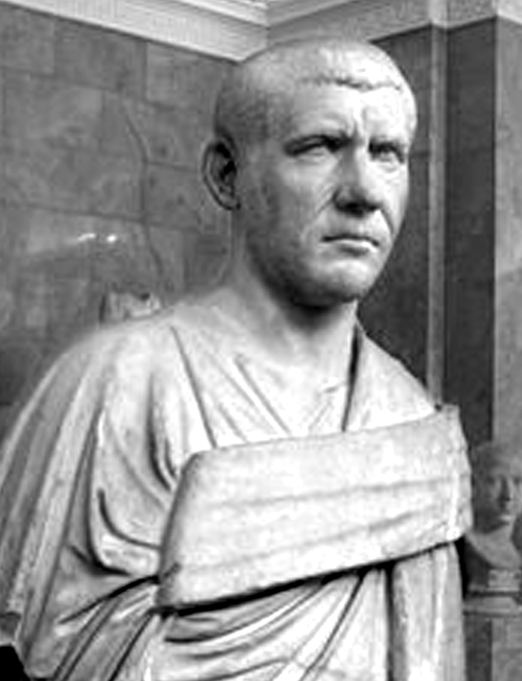

Caesar Philip, first nominally “Christian” emperor

“Now the Britons did not keep Easter at the correct time, but between the fourteenth and twentieth days of the moon – a calculation depending upon a cycle of eighty-four years.” Bede notes further that when presented with the changes in custom then in force throughout the Roman Church, there were “Britons who stubbornly preferred their own customs to those in universal use among the Christian Church.” Early on, custom emerged to convene a church convention during the eight days of Passover and Feast of Unleavened Bread. The church historian Eusebius, writing just after 325 AD, makes it clear that this custom was still in force less than one hundred years before his day in the church of Antioch. Antioch was one of the most ancient and important churches in the East, St. Paul’s home ecclesia, and where the brethren were first called “Christians” (Acts 11:26).

Eusebius records an incident from the life of Caesar Philip (“The Arabian”) who wished to be counted as a Christian in 244 AD.9 The church of Antioch, like all the churches of this period, based their observance on the Jewish custom and observed this festival for its full period. Eusebius called this period the “Paschal vigil” (from the Hebrew Pesach).

Caesar Philip’s penance conformed with custom that favored baptism at the start of Passover. The newly baptized wore a white robe for the week, but at the end of this “Paschal vigil” they were laid aside and street clothes were resumed as everyone returned to the normal pursuits of life. Later, “Easter” (conforming to this pagan name seems appropriate to the changed festival) was established to be always on a Sunday. The Sunday after Easter became known as Dominica in Albis Depositis, the “Sunday the White Garments are set down.” In English church tradition this is the origin of the term “Whitsunday” or “White Sunday.”

Though this movement began with the churches in the East, it took hundreds of years for the changed observance to become uniform. Dionysius Exiguus (ca. 470 to 544), a leading church scholar of Romanian origins, is best known as the inventor of the “Anno Domini” or, “AD” era. He introduced conformity in the calculation of Easter. In 525, Dionysius prepared a table of future dates for Easter and a set of “arguments” explaining their calculation. He did this on his own initiative, not at the request of Pope John.

Although Dionysius stated that the First Council of Nicaea in 325 AD sanctioned his method of dating Easter, the surviving documents are ambiguous. A canon of the council implied that the Roman and Alexandrian methods were the same even though they were not, whereas a delegate from Alexandria stated in a letter to his brethren that their method was supported by the council.

In either case, Dionysius’ method had actually been used by the Church of Alexandria (but not by the Church of Rome) at least as early as 311 AD and probably began during the first decade of the fourth century, its dates naturally being given in the Alexandrian calendar. Thus Dionysius did not develop a new method of dating Easter. At most, he may have converted its arguments from the Alexandrian calendar into the Julian calendar. The resulting Julian date for Easter was the Sunday following the first Luna XIV (the 14th day of the moon) that occurred on or after the XII Kalendas Aprilis (21 March), that is, 12 days before the first of April, inclusive. This formula is still in use today.

How do these systems compare? Using the Catholic Formulation of Dionysius Exiguus, in this year 2008 AD the spring equinox (March 21st) was a Friday, and the full moon came the next day. Hence, there was an unusually early Easter Sunday March 23rd with the start of spring as “Good” Friday, March 21st.

Using the Jewish reckoning, in this year 2008 AD Nisan began with the new moon approximately two weeks after the Spring Equinox. Hence the 14th of Nisan two weeks after that began at sunset on Friday, April 18th.

The unusual conjunction of the equinox and the full moon thus put the two observances out of phase by a full lunar month. It is not an accident that with the anti-Jewish sentiments of the early church, the formula was deliberately chosen so that the two holiday observances would never coincide.

Question Eight

What is the current reckoning of the Memorial dates for the near future?

The Jewish Calendar that dates from the time of Hillel II (359 AD) is the official calendar of the State of Israel. It is used to determine the dates for Passover provided here. It is a lunisolar calendar based on computations rather than visual observations (visual observations of the young crescent moon were used in ancient times).

Passover begins on the same liturgical date, Nisan 15, each year. The dates for Passover for the years 2008-2029 using the civil calendar are based upon this method as calculated by the U.S. Naval Observatory which was employed because it is religiously neutral.10

Note that the Memorial in 2015 is unusual in that it will also coincide with the solar anniversary of our Lord’s sufferings, the Memorial on a Thursday evening, April 2nd, his crucifixion on Friday April 3rd, and the celebration of his resurrection on the following Sunday April 5th. Bro. Redeker observes,

“It is interesting to note that when the dates are set up according to the 19-year cycle of the Jewish calendar, the day of the month for Nisan 13 (calendar date on which our Memorial falls) each year in the cycle is the same, or seldom varies by more than a day or two. Thus this year (2008) our Memorial occurred on April 18th. This was the 11th year in the current 19-year cycle, and the 304th cycle since the (supposed) beginning of the world. The 11th year in the previous cycle was in 1989, and it also fell on April 18th; the 11th year in the next cycle will be 2027, and that will fall on April 20th; etc. This is a recurring phenomenon throughout all the cycles.” 11

The chart at the top of the next column lists dates for the Memorial observance for several years into the future.

– Richard Doctor

(1) “The Memorial Supper – Questions of Interest,” Beauties of the Truth (7:1), February 1996.

(2) Alfred Edersheim, The Temple: Its Ministry and Services, reprinted by Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI (1983) Chapter 11.

(3) Redeker, Charles F., personal correspondence (May 5, 2008); and Redeker, C.F., Foregleams of the Messiah, Zion’s Tower of the Morning Tract Publications (www.zionstower.com, Box 3261, Southfield, MI 48075), originally published 1982, page 16, “The search for leaven.” This valuable reference also includes many helpful diagrams. See also Redeker, C.F., The Memorial Supper, Zion’s Tower of the Morning Tract Publications (2008).

(4) http://www.jewishagency.org/

(5) “Dating the Crucifixion,” Beauties of the Truth (7:1), February 1996.

(6) Redeker, Foregleams of Messiah, op. cit., pages 103-109.

(7) This Augustine is not the famed “Saint” Augustine, Bishop of Hippo and author of City of God.

(8) Bede, A History of the English Church and People , Book 2, Chapter 2.

(9) Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History, Book 6, Chapter 34, “Philip Caesar.” Philip considered himself a Christian, hence the first Caesar who was a “Christian,” well before Constantine. But following his acquisition of supreme power through murder, he found that the church would not lightly dismiss such a sin. “Gordianus had been Roman emperor for six years when Philip, with his son Philip, succeeded him [244 ADJ. It is reported that he, being a Christian, desired, on the last day of the paschal vigil, to share with the multitude in the prayers of the Church, but that he was not permitted to enter, by him who then presided, until he had made confession and had numbered himself among those who were reckoned as transgressors and who occupied the place of penance. For if he had not done this, he would never have been received by him, on account of the many crimes which he had committed. It is said that he obeyed readily, manifesting in his conduct a genuine and pious fear of God.”

(10) http://aa.usno.navy.mil/faq/docs/passover.php. For further information see the Explanatory Supplement to the Astronomical Almanac, ed. Seidelmann, P. K. (1992), Chapter 12, “Calendars,” by L. E. Doggett. Most books on calendars describe the details of the Jewish Calendar.

(11) Redeker, personal communication (May 5, 2008).